Industry Stories

Container ship industry finds flexibility eclipses efficiency, for now

International ocean carriers entered 2020 with an expense problem and a profit problem.

Global maritime regulators mandated a shift to cleaner, low-sulfur fuel beginning Jan. 1. Analysts predicted that shipping fuel prices could rise 25%. Even before that added cost, vessel owners had struggled to make money. Financial data from 12 multi-billion-dollar shipping companies shows a median annual profit margin of 0.2% and the largest margin at less than 3%, according to analysis by Infosys Knowledge Institute.

Anticipating higher fuel costs and needing to generate fatter margins, the industry for years built bigger ships and expanded ports. The Panama Canal was widened in 2016. New Jersey authorities in 2019 raised the Bayonne Bridge to accommodate larger ships. In April, carrier Hyundai Merchant Marine launched the new world’s largest container ship.

By spring, the COVID-19 pandemic had flipped the industry’s fears and undercut their strategy. With the broad shutdown of other transportation, fuel costs have plummeted. While low-sulfur diesel sold at the port of Los Angeles for more than $2 a gallon in January, it plummeted to 57 cents per gallon in April. (Ocean carriers buy fuel by the ton, but their prices have dropped in the same pattern.)

With social-distancing shutdowns and recession on the horizon, vessel owners now face falling demand for cargo spots just as they build larger and larger ships.

Instead of building scale and efficiency, ocean carriers now must find ways to be flexible during a period of uncertain shipping volumes and rates. Carriers don’t want to sail a ship that’s not full. So in the face of decreased demand, carriers reduce capacity by delaying planned sailings.

The Far East-to-North America shipping trade volume bottomed out at just more than 600,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) for sailings departing the week of Feb. 24, according to data from eeSea, a Copenhagen-based maritime and supply chain intelligence company (Figure 1). That works out to slightly more than 60% of that week’s full capacity for the trade lane, according to eeSea’s calculations.

Figure 1. Shipping capacity since the pandemic has been mostly lower than normal despite a huge reduction in fuel costs.

Source: eeSea, U.S. Energy Information Administration

As China began reopening in March, production resumed and ships filled. By April 13, the Far East-North America trade lane reached full capacity, according to eeSea. But what pushed shippers back to that level reflects pre-COVID demand and planned delays around the Lunar New Year holiday in late January. As one shipping insider explained, U.S. retailers ordered their summer clothes in the winter of 2019.

Since that full-capacity week in mid-April, carriers have been cutting back. Data from eeSea shows canceled sailings extending through the end of June. On average, 55 to 60 ships leave an Asian port each week for a North American one. In May and June, carriers have canceled seven to 13 sailings per week.

In typical times, ship owners cancel sailings two months before their scheduled departures, but this year, companies have given as little as two weeks’ notice, noted Simon Sundboell, CEO of eeSea. This newfound flexibility is going both ways. On May 14, an alliance of shippers Hapag Lloyd, ONE, and Yang Ming reinstated a pair of late-May sailings.

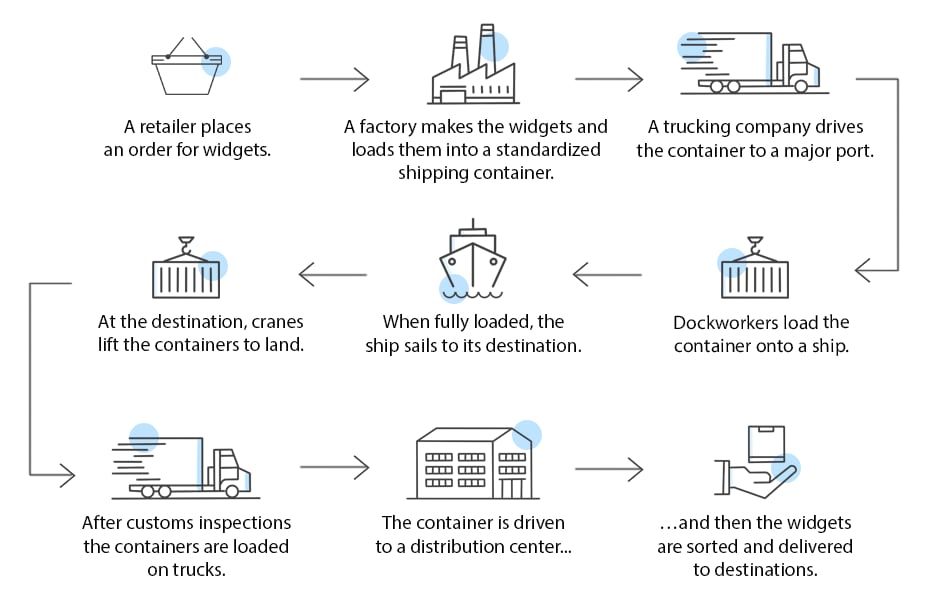

Figure 2. How container shipping works

Source: World Shipping Council

Cargo owners bear more of the added cost for this flexibility than the carriers do, which is a reversal of the industry’s prevailing power dynamics. Product buyers who sign up to deliver thousands of containers to a shipping line don’t face a financial penalty or pushback from the shipper if they deliver less than promised, Sundboell said.

“There’s always been sort of a ‘If you don’t show up or commit volumes, don’t expect me to be on time or commit to the weekly departure I’ve promised you,’” tension between carriers and cargo owners such as big discount retailers, he explained.

Carriers certainly would like to maintain the flexibility to cancel sailings on shorter notice, Sundboell said, noting that carriers have managed through the process of withdrawing capacity better than most would have thought. Can carriers continue finding a decent balance in the face of uncertain supply and demand?

Years of pursuing larger scale and efficiency does not bode well for that. Hyundai Merchant Marine’s new ship has a record capacity of 24,000 TEUs, and is the first of 11 of that size it has on order.

International shipping can deal with low shipping volumes by canceling sailings, or it can deal with low shipping rates by sailing very full ships. But it can’t do both. Reduced demand caused by the pandemic could leave the container fleet underutilized for years to come. Their high cost may put even greater strain on carriers operating on already slim margins.